Understanding Bursitis: What It Is and How to Treat It at Home

Introduction

Most people have heard of bursitis, but few really understand what a bursa is. These small, fluid-filled sacs are located throughout the body — especially near joints — and act as cushions between bones, tendons, and muscles. Their main role is to reduce friction and help joints move smoothly.

When one of these sacs becomes inflamed or irritated, the result is bursitis. This condition can be frustrating, especially when it affects your ability to sleep, work, or move without pain. Fortunately, most cases respond well to simple, evidence-based strategies you can implement at home. This article will explain what bursitis is, explore common types, and walk you through how to manage it with confidence.

What Is a Bursa?

A bursa is a thin, slippery sac filled with synovial fluid. You can think of it as a small pillow that cushions moving parts, like tendons or skin, from rubbing against bones. Healthy bursae help reduce wear and tear on your joints and allow for smooth, pain-free movement.

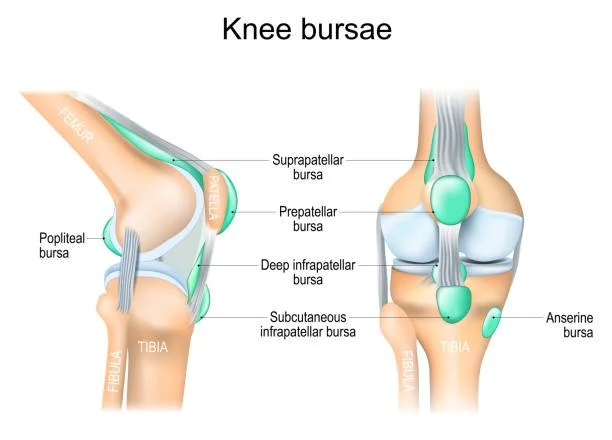

Common areas where bursae are found include:

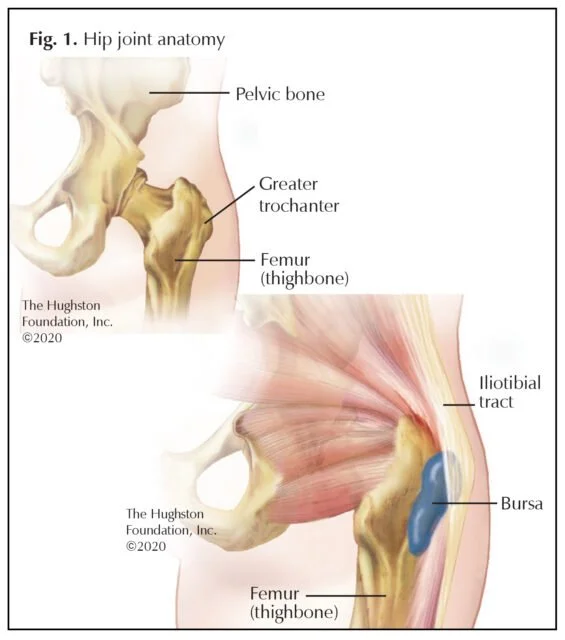

Hips (greater trochanter)

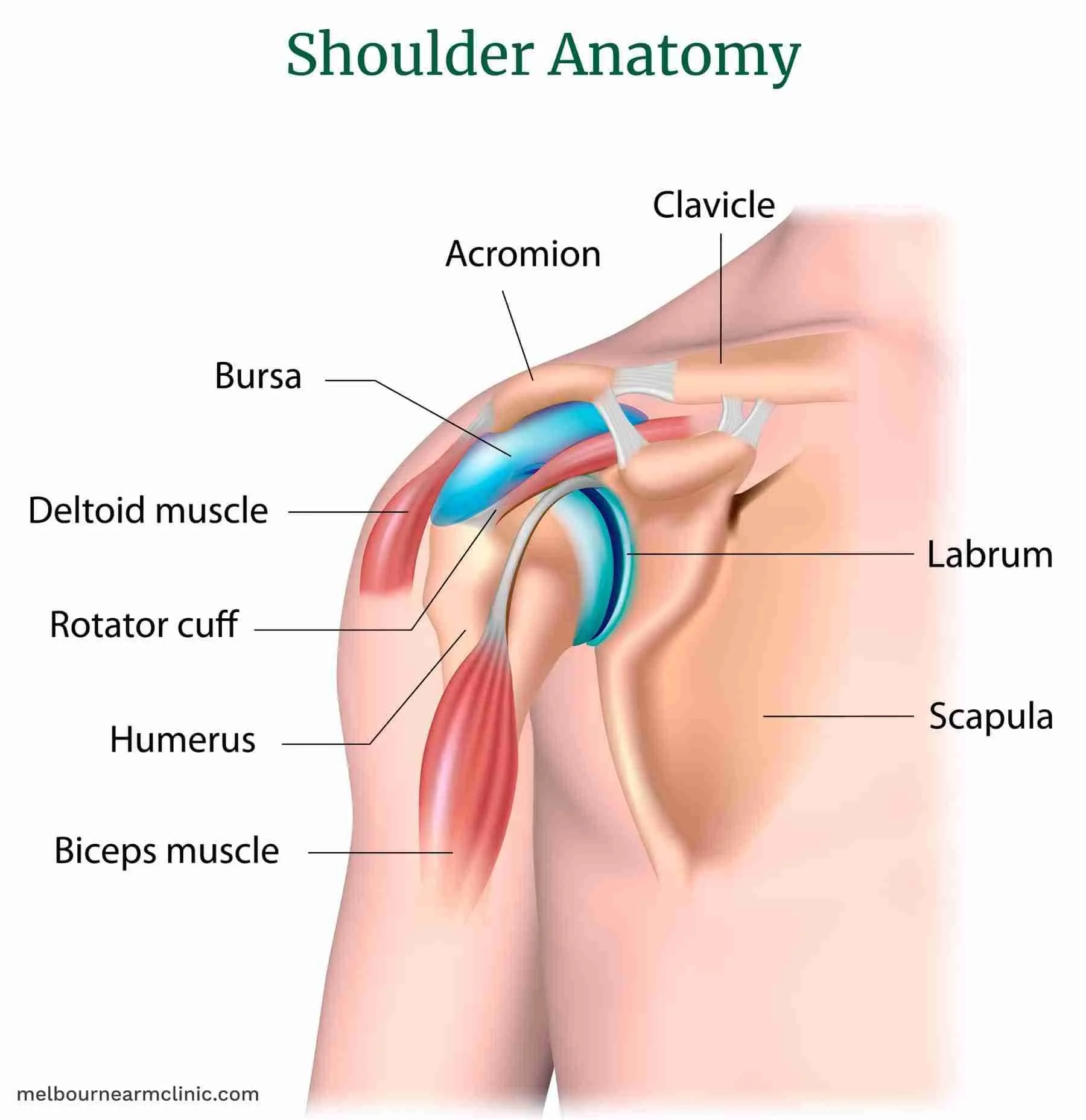

Shoulders (subacromial)

Elbows (olecranon)

Knees (prepatellar, pes anserine)

Heels (retrocalcaneal)

There are over 150 bursae in the human body, but only a handful commonly cause symptoms.

What Is Bursitis?

Bursitis is the inflammation or irritation of a bursa. This can happen gradually due to repetitive stress or suddenly from an impact or infection. When inflamed, the bursa produces excess fluid, leading to pain, swelling, and limited motion.

Causes include:

Repetitive motion or overuse (e.g., climbing stairs, throwing, kneeling)

Direct pressure or trauma (e.g., bumping the elbow or falling on the hip)

Underlying biomechanical issues (e.g., poor posture, muscle imbalances)

Systemic conditions (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, gout)

Infection (septic bursitis, especially in superficial locations like the elbow or knee)

Symptoms:

Localized pain and tenderness over the bursa

Swelling that may be visible or feel like a soft lump

Warmth or redness (especially if infected)

Pain with certain movements or positions (e.g., lying on your side, kneeling)

Differential Diagnosis:

It’s common to confuse bursitis with tendinitis or arthritis:

Tendinitis causes pain with muscle contraction and loading (e.g., lifting a weight).

Arthritis causes deeper joint pain and stiffness, often with morning stiffness.

Bursitis pain is often most noticeable with pressure (like resting on the area) or specific positions.

Most Common Types of Bursitis

While bursitis can affect many parts of the body, the following are the most common and relevant to daily life.

Trochanteric Bursitis (Hip)

Pain on the outer side of the hip or thigh

Worse when lying on that side, climbing stairs, or standing for long periods

Common in women and runners; often linked to weak glute muscles, pelvic asymmetries, or IT band tension

May radiate down the side of the leg, mimicking sciatica

Subacromial Bursitis (Shoulder)

Pain when reaching overhead or behind the back

Frequently coexists with impingement or rotator cuff problems

Nighttime pain is common, especially when lying on the affected side

May cause a painful arc of motion (pain between 60°–120° of elevation)

Olecranon Bursitis (Elbow)

Swelling at the tip of the elbow — can be dramatic and dome-like

Often painless unless infected or under pressure

Caused by prolonged leaning or trauma (e.g., bumping the elbow on a desk)

Important: High risk of septic bursitis — redness, warmth, and fever require medical evaluation

Prepatellar Bursitis (Knee)

Swelling over the front of the knee (just above the kneecap)

Common in those who kneel frequently (e.g., carpet layers, gardeners)

Can become chronic if underlying pressure isn’t addressed

Like olecranon bursitis, it’s prone to infection

Additional types (briefly):

Pes anserine bursitis – Pain on the inside of the lower knee, common in overweight individuals or runners

Retrocalcaneal bursitis – Pain behind the heel, often from tight footwear or Achilles tightness

How Bursitis Is Diagnosed

Diagnosis is primarily clinical, meaning it’s based on your story and a physical exam.

What your provider looks for:

Clear tenderness over the bursa

Swelling localized to one area

No joint instability or signs of muscle injury

No significant loss of motion (though pain may limit it)

Imaging:

Ultrasound: Helps detect bursal fluid or rule out other issues

MRI: Rarely needed unless another problem is suspected (e.g., tendon tear)

When to consider lab testing:

In cases of possible infection (fever, warmth, drainage)

If a systemic inflammatory condition is suspected

Home Management Strategies

You can often manage bursitis effectively at home, especially in mild to moderate cases. Here’s how:

1. Inflammation Control

Ice: 15–20 minutes, 2–3x/day, especially early on or after activity

NSAIDs: Ibuprofen or naproxen can help - check with your doctor if you have GI, kidney, or heart risks

Activity modification: Temporarily reduce aggravating movements

Short-term support: Padded sleeves or braces may help reduce stress on the area (avoid long-term reliance)

👉 Interested in research backed techniques to address inflammation on your own? See my article on how to address chronic inflammation

2. Positioning & Pressure Relief

Use cushions when sitting or lying down to avoid compressing the bursa

Side sleepers: pillow between knees for hip bursitis

Office workers: elbow pads or forearm supports to reduce elbow pressure

Avoid kneeling or use foam pads if necessary

3. Gentle Mobility & Circulation

Movement promotes synovial fluid flow and prevents stiffness

Begin with low-resistance motion:

Shoulder: pendulums, wall slides

Hip: standing leg swings, slow stair stepping

Knee: heel slides, seated leg extensions

Avoid deep stretching or ballistic movements during flare-ups

4. Strengthening to Prevent Recurrence

Once pain improves:

Target weakness around the affected joint

Hip: glute bridges, side-lying abduction, clamshells

Shoulder: scapular stabilizers (rows, Ys, wall angels)

Knee: quad sets, step-ups, mini-squats

Use slow, controlled reps — avoid compensating with surrounding muscles

Focus on form > load

👉 Want to know the best way to progress your exercises? I have written an article specifically on how to progress from a rehabilitation perspective.

5. Ergonomics & Daily Habits

Adjust workstation or routine activities to reduce repetitive strain

Take movement breaks throughout the day

Evaluate footwear and gait (especially with hip/knee pain)

Sleep position matters: find a pain-free setup and support with pillows

⚠️ When to See a Doctor or PT

While many cases improve with self-care, some signs warrant medical input:

Seek help if you experience:

Persistent or worsening pain after 10–14 days of home treatment

Redness, heat, or fever (possible infection)

Recurrent flare-ups that interfere with daily life

Loss of strength, function, or sleep

Unclear cause or multiple painful sites

Physical therapy can help:

Address contributing movement faults

Design a progressive strengthening plan

Teach posture and ergonomic strategies

Use modalities like ultrasound or taping (as appropriate)

Myths and Misconceptions

Let’s clear up a few common misunderstandings:

"You should stop moving completely."

➤ Movement helps healing. Just avoid painful or high-impact activities.

"Cortisone is the only way to fix it."

➤ It can help in stubborn cases, but often isn’t necessary.

"It’s just part of getting older."

➤ Aging tissues may be more prone, but prevention and treatment still work.

"It’ll go away on its own."

➤ Possibly — but without correcting the cause, it’s likely to return.

“it’ll never go away.”

Bursitis can be frustrating to get ride of, but with proper offloading and support it can go away completely

Final Thoughts

Bursitis doesn’t have to be a long-term problem. With early attention, smart positioning, and a gradual return to movement, most people make a full recovery. The key is knowing when to rest, when to move, and how to address the root cause.

If you’ve been dealing with stubborn bursitis, don’t give up. Physical therapy and exercise can be a game changer, especially if you’ve been stuck in the cycle of rest, flare-up, and frustration. Empower yourself with the right tools and mindset, and you’ll be well on your way to lasting relief.

Additional Resources:

Understanding Inflammation: How to Heal Smarter, Not Just Harder

Rehab Exercise Progression: A Patient’s Guide to Safely Advancing Your Recovery

Ice vs Heat for Injury: A Physical Therapist’s Guide to Pain & Swelling Relief

References:

Pianka MA, Serino J, DeFroda SF, Bodendorfer BM. Greater trochanteric pain syndrome: Evaluation and management of a wide spectrum of pathology. SAGE Open Medicine. 2021;9. doi:10.1177/20503121211022582

Lustenberger DP, Ng VY, Best TM, Ellis TJ. Efficacy of treatment of trochanteric bursitis: a systematic review. Clin J Sport Med. 2011;21(5):447-453. doi:10.1097/JSM.0b013e318220f397

Kjeldsen T, Hvidt KJ, Bohn MB, et al. Exercise compared to a control condition or other conservative treatment options in patients with Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Physiotherapy. 2024;123:69-80. doi:10.1016/j.physio.2024.01.001

Williams CH, Jamal Z, Sternard BT. Bursitis. [Updated 2023 Jul 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513340/

Bird PA, Oakley SP, Shnier R, Kirkham BW. Prospective evaluation of magnetic resonance imaging and physical examination findings in patients with greater trochanteric pain syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(9):2138–2145.